From the Archives: Dazed Feb 2013 issue: The Joy of Sets

Welcoming in the new season, fashion’s elite scenographers tell us the secrets to creating runway alchemy.

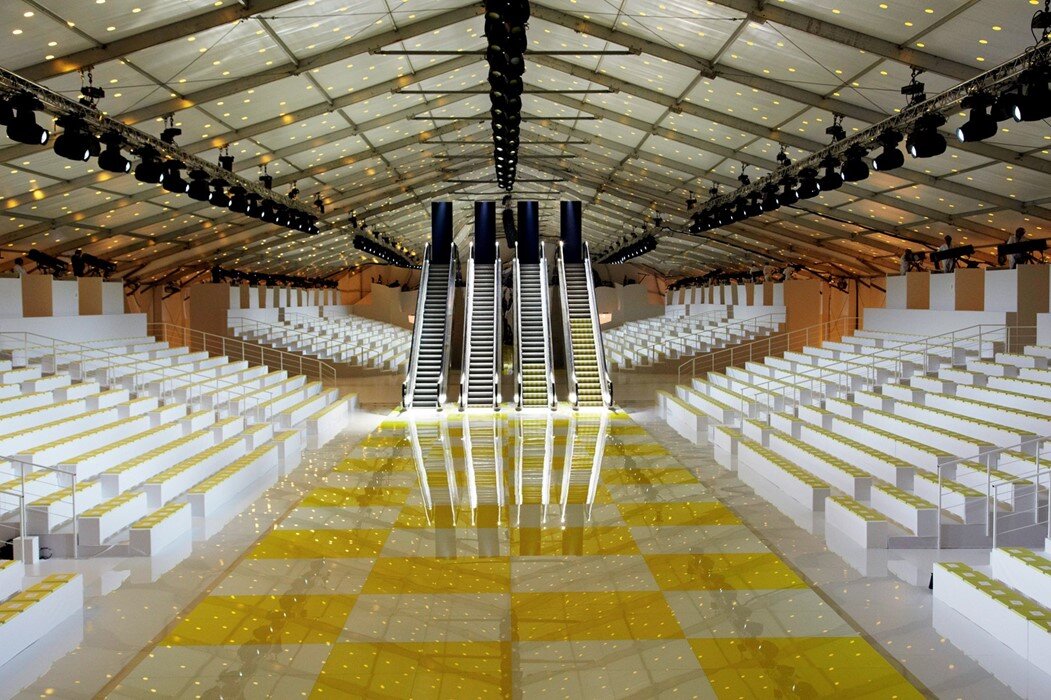

If you’re ever looking for a compelling argument against the miniaturisation of the fashion show – with its blurry instagrams and endless tweets – and for the continued preservation of the widescreen live spectacle of the runway, consider this single image from the recent SS13 Louis Vuitton presentation: models dressed in Marc Jacobs’ geometric silhouettes, descending in pairs (a nod to Diane Arbus’s photographs of twins) down a gleaming bank of escalators that empty out onto a giant tessellated yellow-and-white-checked runway. A world away from the romantic nostalgia of last season’s steam trains, the graphic modernism of the set hit upon the season’s themes as well as scoring Jacobs another critical success.

Jacobs is no stranger to working with artists for his runway shows – sculptor Rachel Feinstein created a “Marie Antoinette version of a ruin” for his eponymous label’s AW12 show, while Vuitton’s SS08 show saw Richard Prince’s Nurse paintings brought to life on supermodels like Stephanie Seymour and Naomi Campbell. For this latest show, a site-specific installation was created by abstract minimalist Daniel Buren, whose controversial 1986 work “Les Deux Plateaux” – an arrangement of columns in a grid in the courtyard of the Palais Royal in Paris – provided the initial inspiration. “The square and the grid are repeated motifs in Buren’s work while the checks relate to Louis Vuitton’s own geometric Damier pattern,” Jacobs says. “Also, Buren’s famous work is in the centre of Paris, the home of Louis Vuitton, which is at the heart of the house today and throughout its history.”

For Buren, who has collaborated with Nina Ricci and Hermès, fashion and art make natural bedfellows. “The world of fashion has a very long history of direct collaboration with the art world,” he says. “I believe that for at least 20 years we have been at the very top level of collaboration between these two worlds.” It was the very ephemeral yet public nature of doing a high-profile fashion show that attracted him to the project. “I think of these works as specific exhibitions that could just as well be shown within a museum or a gallery. The difference is that the exposure given by these fashion houses with a worldwide presence is bigger in public reach than any single museum in the world.”

It’s a far cry from over a century ago, when British designer Lucile (aka Lady Duff-Gordon) popularised fashion shows as we know them today, organising biannual presentations of her clothes in Europe and America at which models would slowly parade up and down the catwalk while a lone voice intoned the specifics of each look. In the last 20 years, the concept of fashion shows has evolved from mere tradeshow mechanism to something approaching an artform. They can take anywhere from three days to six months to execute, at times involving hundreds of craftsmen, all to create 12 minutes of alchemy that, at their finest, can make us dream of ourselves in clothes and make the fashion experience come alive. The best shows are a highly concentrated collision of theatre, emotion, explosiveness and, often, good old-fashioned spectacle. Against all odds, designers and scenographers strive to preserve and inspire a sense of wonder and enchantment.

Of course, it was the internet that changed everything; YouTube and livestreaming now allow a virtual front-row seat for millions of people watching at home, placing a greater importance on the show as theatre. Fashion-show producer and Villa Eugénie founder Etienne Russo has embraced this change and the possibility of his work going viral. “What’s fantastic for me,” he says, “is that the people who pull the strings now are the consumers, and they can be part of it. Today the person who wants to buy the fashion gets the information. They can get educated. That means more pressure on us because the message has to be crystal clear and every single detail has to be right.”

Matching Vuitton in the Napoleonic excess stakes, Chanel’s Karl Lagerfeld has in recent seasons animated a monumental roaring lion in the middle of the Grand Palais (AW10) and filled the haute-couture salons with thousands of delicately cut paper flowers (SS09), creating epic, immersive experiences that challenge the boundaries of fantasy. Speaking from Scotland, where he has created a darkly romantic mise-en-scène in the historic Linlithgow Palace for Chanel’s travelling Mètiers d’Arts extravaganza, Russo pays tribute to Lagerfeld’s ceaseless imagination, “It’s like he never ages. Karl designs and thinks of everything. I am just happy to be the hands behind it.”

Of course, Russo is much more than this. Twenty-five years since he produced his first fashion show for his friend Dries van Noten, he has a reputation as one of the most innovative and forward-thinking producers in the industry. He can do understated (his shows for Céline are masterclasses in spare and clean) or emotional (a spine-tingling celebration at Lanvin of Alber Elbaz’s tenth anniversary). “Some people want to whisper it and some want to shout it out loud. Spectacle is not right for everybody. It’s about doing the right thing, finding the right balance and doing things the right way.” He hit a creative jackpot working with Carol Lim and Humberto Leon at the newly energised Kenzo, for which he masterminded an AW12 takeover of the Université Pierre et Marie Curie, turning it into a space-age mall where models danced to a remix of Dolly Parton’s “9 to 5”. It was a smart update of the original Jungle Jap shows by founder Kenzo Takada, remembered as the first time prêt-àporter outshone haute couture in presentation. “The idea was to do a show in a different way that was fresh and young,” Russo says. “We wanted to bring back the spirit of Kenzo but in a contemporary way, with no nostalgia. The roots were transformed into what a kid wants today.”

Visual pyrotechnics are one thing, but as Thierry Dreyfus, founder of Paris-based production studio Eyesight, would argue, what about the light? That elusive, often underappreciated quality is the specialty of Dreyfus, who rose to prominence with his work with Helmut Lang in the 90s. His graphic layering of whiteon- white light set a new standard and creative direction for the brand. He protests that he is not an artist, merely “a mercenary”, but he’s being modest. This is a man who plunged the Notre Dame into darkness only to make it glow from within for the 2010 Nuit Blanche, and illuminated the 2005 re-opening of the Grand Palais for 500,000 people. “Light doesn’t have words or speak intellectually,” he says. “It is reflecting on the girl, the boy, the floor, the back and the set – it has to be a unity. It is about emotion. What you try to express is the way you see the designer.”

This season he worked on 21 shows, including Jil Sander’s much-anticipated return to her own label after eight years, for which he created a stark white set consisting of an oval stage mirrored under another oval on the ceiling – a tribute to one of his heroes, Brâncusi. “It was all about the perfection of the curve, an oval, feminine shape.” The effect was striking but discreet, mirroring Sander’s own subtle touch. “The elements are all there but disappear to emphasise the collection. The perfection is so you forget and concentrate on what’s ahead of you.”

While it is often the scenographer’s job to spell the designer’s intentions out large, it can equally be to create another layer of the puzzle. For Miuccia Prada, a literal translation of her seasonal preoccupations would never do. A designer who revels in completely upending expectations and preconceived notions, she found a kindred spirit in Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas. The AMO division of his firm has been collaborating on Prada’s catwalk shows since 2004, turning the traditional runway on its head. Each season the Fondazione Prada in Milan is transformed, often in ways that dispense with the traditional hierarchies of fashion shows. “For us designing a catwalk is almost like designing a temporary public space,” AMO’s Ippolito Pestellini says. “You have to seat 700 people for 12 minutes in an interesting and different way.”

Work begins on the set virtually in parallel with the design of the collection, so “each one amplifies each other. We create a concept both geometrically or through scenography that they can react to. There’s always the intention to wrongfoot the visitors – to make something not completely clear or evident at first glimpse.” Prada’s AW12 men’s show was a case in point. A film-star-studded cast of the likes of Adrien Brody and Gary Oldman strode across a giant red carpet like pawns in a real-life chess game – Ms Prada’s meditation on “male power”.

AMO went to Soviet architecture for references. “We were really looking into the architecture of cultures that expressed power in society,” Pestellini says. “It’s very conceptual at the beginning and that’s why the results are always so different. Prada and AMO work in a similar way: everything starts from research. It’s about a concept that emerges in multiple configurations. There’s not really a method – it’s always a surprise.”

Dreaming up million-dollar events to rival Hollywood blockbusters is par for the course for the megabrands, but whither the younger, independent designers? Bureau Betak for Rodarte and Simon Costin for Gareth Pugh are proof that ingenuity and storytelling are not synonymous with budget. Rodarte’s Kate and Laura Mulleavy take obsessions and minuscule fascinations from their lives – from the redwood forests of California to RPG fantasy games – to create an intensely personal vision. Their long-term collaborator, Alexandre de Betak, helps them translate their myriad influences in their usual intimate setting of the Gagosian in New York. “Alex brings an ingenuity to our shows,” the sisters enthuse, “utilising space and light in an innovative and creative way. He understands our minimal inclinations in regards to environment and uses his knowledge of art and visual cultures to bring our vision to life every season.”

Although his production company, Bureau Betak, stages mega-budget marvels for the likes of Viktor & Rolf and Dior, he relished the chance to work on a smaller scale when the Mulleavys approached him five years ago. “When you work in a job like mine, it’s very important to stay in touch with creativity and with smaller, more human-sized projects,” muses de Betak. “When I first met Kate and Laura, I was completely amazed by their original talent. They invent in their own world.” It’s his job to highlight the duality between harshness and lightness that is the essence of Rodarte. “I’ve made sure that from the first show to the last, there’s always an element that’s carried over. It’s important to put in this linkage that has all these qualities that make them Rodarte. There’s never anything literal – when we mix it all together, what comes out is then open to everyone’s interpretation.”

Gareth Pugh has excelled in consistency of vision. Since relocating his shows to Paris from London, what he may have lost in anarchic, anything-goes rawness he’s gained in polish and showmanship. Working with his close team of stylist Katie Shillingford (Dazed’s senior contributing fashion editor), music man Matthew Stone, make-up artist Alex Box and set designer Simon Costin, Pugh has been finding new ways to translate his assured vision. In a way, collaborating with Pugh brought Costin back to an earlier time, when he was art director for another British enfant terrible, Alexander McQueen. “You find yourself working in a more fluid and spontaneous way, free to suggest mad ideas,” Costin says, “like an inflatable catwalk, which many a designer would recoil at in case it didn’t work or models fell over.” A smaller budget often means thinking on your feet. “You end up being creative in ways you might not have expected, like blocking the entrance to the catwalk with a giant weather balloon which gets burst by the first model to appear!”

It may be a century since the runway show was invented as the ritual that beats at the heart of fashion, but these artists are finding new ways to set pulses racing. The art of scenography is a strange one: part architecture and interpretation of designers’ dreams, part witchcraft, with a dash of Hollywood bravado thrown in, all to create transient experiences that can endure in the mind. If there can be a sense of bittersweet melancholy for the audience when a show is over, these artists remain relentlessly forward-looking. “I don’t want to talk about the past,” Dreyfus says. “When you’re done with an installation, it’s in the memory of the people.” But like the designers they work with, their work is never quite done. “My favourite show?” Dreyfus ponders for a minute before saying with a smile, “Always the next one.”